By Rosanna Brunwin, Intern 2015

TW: This piece candidly discusses self-harm, which may be triggering for some readers.

Despite statistically affecting one in four of us, mental health is shrouded in stigma and often goes undiscussed. Unless your mental health problems manifest in self-harm — then suddenly it’s everybody’s business.

When I was 14 and in high school, it seemed like every other teenage girl was cutting themselves. And at one point, it was even considered — alarmingly — fashionable and cool. In fact, an estimated 13 percent of young people hurt themselves on purpose at some point during their teenage years. For some, though, it becomes more than just a way of expressing teenage angst, or a method of attracting attention and sympathy when it feels like no one is listening. Self-harm becomes an addiction, a coping method, a way of survival.

For me, self-harm became a part of who I was.

The No. 1 question was always, Doesn’t it hurt? Weirdly, no. When you cut yourself, a surge of endorphins are released. These endorphins inhibit the transmission of pain signals and essentially provide happy chemicals instead. This also happens when you exercise, have an orgasm, look at someone you love, or eat chocolate.

Endorphins themselves are not necessarily addictive; we all like them. The post-orgasm bliss? The after-workout buzz? It feels good. Really good. It makes you feel good about yourself. And that’s what self-harm did for me. When I cut myself, I didn’t just feel good — I actually felt. Cutting myself made me feel less disconnected and numb. It made me able to face the world. Despite people linking it to suicide so frequently, I couldn’t survive without it.

10 years on, and I am left with a plethora of scars and marks and bumps. I’m not particularly proud of what I’ve done. Sometimes the magnitude of the harm and pain I’ve inflicted on myself is very difficult to manage and the sight of my scars makes me cry. I feel I ought to write now about how the scars on my body remind me of what a strong person I have become, and how accepting that has been a really important part of my “journey to recovery.” But in reality, most of the time I forget that they are there.

And I wish the rest of the world didn’t always need to talk about it.

I no longer feel the urge to cover my scars. It is my body, and I do not feel the need to conceal it under long-sleeved shirts or cardigans or hoodies. The preconceived misconceptions many people have should not dictate what I choose to wear. The scars on my arms do not make me weird or dangerous — many more of us self-harm than we realize.

Self-harm doesn’t just exist as cutting yourself. It takes on various forms: burning yourself, reckless drug-taking and drinking, risky sex, dangerous driving, punching walls, etc. But for some reason, taking a blade to your skin crosses the line and becomes part of what the “crazy” people do.

Society seems to have much more of a problem with self-harm in the cutting sense than it does with any other type of destructive behavior. When somebody reaches for a bottle of wine after a stressful day at work, they are unwinding and relaxing. But when someone cuts themselves, that’s when they’ve crossed a line.

This is largely because of the association between cutting and death. There is a huge lack of differentiation between self-harm and suicide in public and medical discourse. Until the Suicide Act came into play in Britain in 1961, self-harm was categorized as a failed suicide attempt. At the time, this meant it was illegal, and even punishable by imprisonment. Fortunately, the decriminalization of suicide in 1961 meant that self-harm is no longer considered a failed suicide attempt, nor is it a criminal act. However, it continues to be labelled a mental health issue, making it rife with stigma.

We recognize that we should not judge people on their appearance. But for some reason, the physical effects of some mental health problems seem not to be included. A person with scars on their arm wearing a tee-shirt seems to also be wearing a sign declaring they wish to be bombarded with questions. Sometimes, despite how obvious it is, people ask me what my scars are from, like they simply want to make things awkward. Or they begin to tell me that they too once self-harmed. Sometimes they even offer me unrequested advice, telling me I’m much better than that and I don’t need to do that because I can always talk to them … despite having only known them for 10 minutes.

Self-harm is a coping mechanism, and we need to stop judging people for using it. We know it comes in many different forms, and that mislabelling it as a failed suicide attempt has added to its stigma. But that was half a century ago. And the stigma needs to go.

I am not “brave” because I don’t cover my scars. I am brave because I no longer associate my self-worth with my physical appearance. The more people begin to realize this and stop hiding themselves, the more people will understand. Hopefully, one day the stigma around self-harm might just disappear.

“It is so important to recognize that there is always hope; that people’s lives and circumstances can and do improve, and that something as profound yet simple as acceptance can have powerfully transformative impacts.” — Kay Inkle

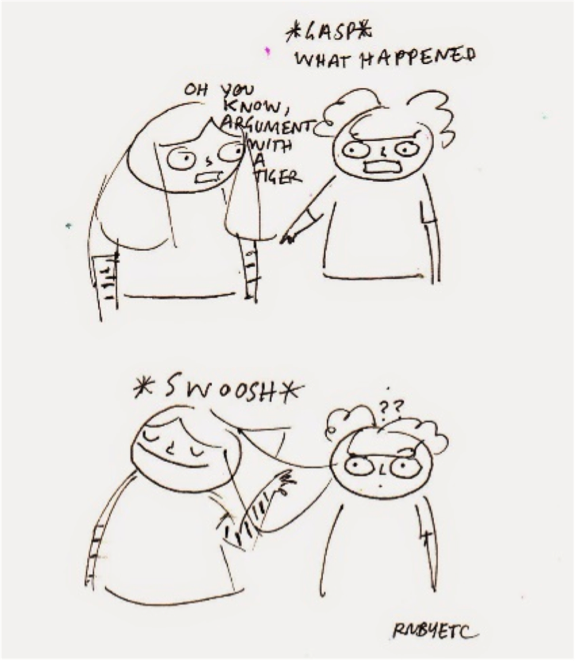

So let’s stop with the flippant “slit your wrists” comments and the unnecessary staring. And next time someone loses all cognitive ability and asks what happened to your arms, this comic has the right idea for a response: